Eddystone Lighthouses

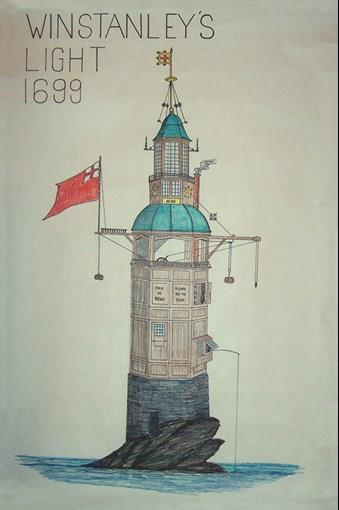

Winstanley Light 1699

The first lighthouse on Eddystone Rocks was an octagonal wooden structure built by Henry Winstanley. The lighthouse was also the first recorded instance of an offshore lighthouse. Construction started in 1696 and the light was lit on 14 November 1698. During construction, a French privateer took Winstanley prisoner and destroyed the work done so far on the foundations, causing Louis XIV to order Winstanley’s release with the words “France is at war with England, not with humanity”.

The lighthouse survived its first winter but was in need of repair, and was subsequently changed to a dodecagonal (12 sided) stone clad exterior on a timber-framed construction with an octagonal top section as can be seen in the later drawings or paintings. The octagonal top section (or ‘lantern’) was 15 ft (4.6 m) high and 11 ft (3.4 m) in diameter, its eight windows each made up of 36 individual glass panes. It was lit by ’60 candles at a time, besides a great hanging lamp’.

Winstanley’s tower lasted until the great storm of 1703 erased almost all trace on 8 December. Winstanley was on the lighthouse, completing additions to the structure. No trace was found of him, or of the other five men in the lighthouse

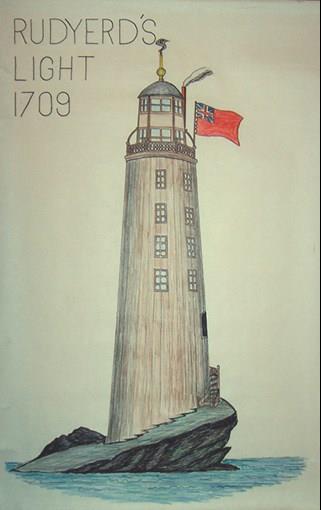

RudyerD Light 1699

Rudyard’s lighthouse, in contrast to its predecessor, was a smooth conical tower, shaped ‘so as to offer the least possible resistance to wind and wave’. It was built on a base of solid wood, formed from layers of timber beams, laid horizontally on seven flat steps which had been cut into the upper face of the sloping rock. On top of this base rose several courses of stone, interspersed with further layers of wood, which was designed to serve as ballast for the tower. This substructure rose to a height of 63 feet (19 m), on top of which were raised four storeys of timber. The entire structure was sheathed in vertical wooden planks and anchored to the reef using 36 wrought iron bolts, forged to fit deep dovetailed holes which had been cut in the reef. The vertical planks were installed by two master-shipwrights from Woolwich Dockyard and were caulked like those of a ship. The tower was topped with an octagonal lantern, which brought it to a total height of 92 feet (28 m). A light was first shone from the tower on 8 August 1708 and the work was completed in 1709. The light was provided by 24 candles. Rudyard’s lighthouse proved more durable than its predecessor, surviving and serving its purpose on the reef for nearly 50 years.

In 1715 Captain Lovett died and his lease was purchased by Robert Weston, Esq., in company with two others (one of whom was Rudyard).

On the night of 2 December 1755, the top of the lantern caught fire, probably through a spark from one of the candles used to illuminate the light, or else through a fracture in the chimney which passed through the lantern from the stove in the kitchen below.[9] The three keepers threw water upwards from a bucket but were driven onto the rock and were rescued by boat as the tower burnt down. Keeper Henry Hall, who was 94 at the time, died several days later from ingesting molten lead from the lantern roof. A report on this case was submitted to the Royal Society by physician Edward Spry, and the piece of lead is now in the collections of the National Museums of Scotland.

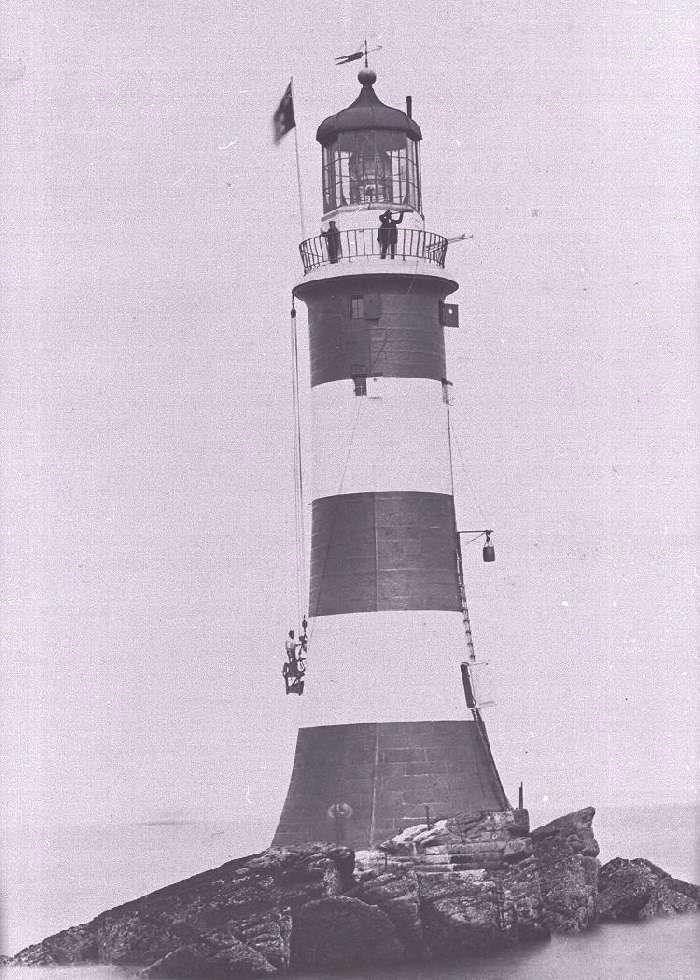

SMEATON Light 1699

Work began on the reef in August 1756, with the gradual cutting away of recesses in the rock which were designed to dovetail in due course with the foundations of the tower. During the winter, the workers stayed ashore and were employed in dressing the stone for the lighthouse; work then resumed on the rock the following June, with the laying of the first courses of stone. The foundations and outside structure were built of local Cornish granite, while lighter Portland limestone masonry was used on the inside. As part of the construction process, Smeaton pioneered ‘hydraulic lime‘, a concrete that cured under water, and developed a technique of securing the blocks using dovetail joints and marble dowels. Work continued over the course of the following two years, and the light was first lit on 16 October 1759.

Smeaton’s lighthouse was 59 feet (18 m) high and had a diameter at the base of 26 feet (7.9 m) and at the top of 17 feet (5.2 m). It was lit by a chandelier of 24 large tallow candles.

In 1877 it was resolved to build a replacement lighthouse, following reports that erosion to the rocks under Smeaton’s tower was causing it to shake from side to side whenever large waves hit. During construction of the new lighthouse, the Town Council of Plymouth petitioned for Smeaton’s tower to be dismantled and rebuilt on Plymouth Hoe, in lieu of a Trinity House daymark which stood there

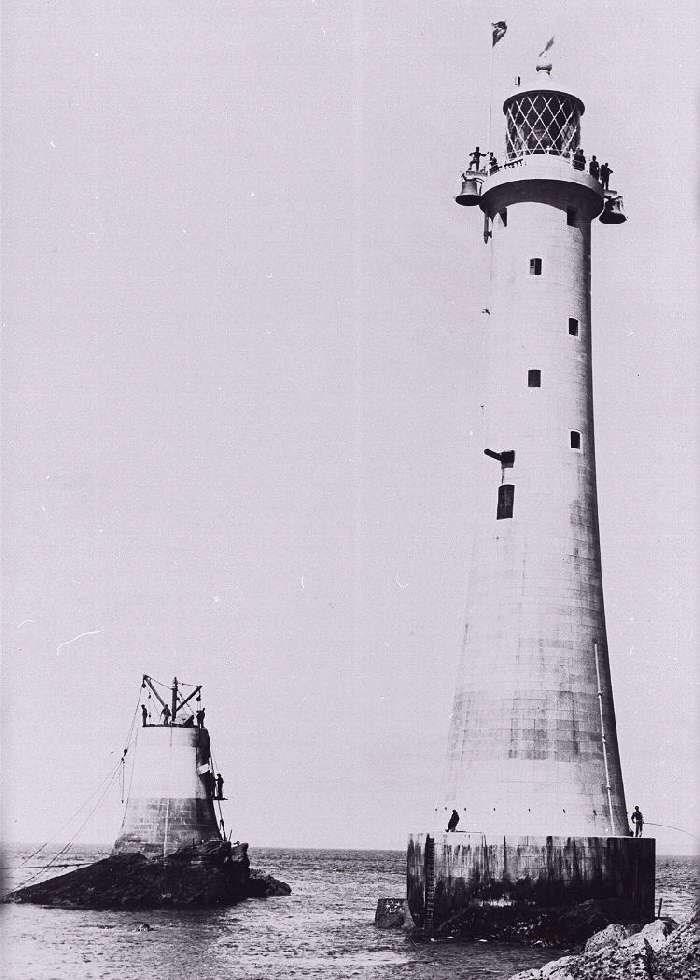

Douglass Light 1882

By July 1878 the new site, on the South Rock was being prepared during the 3½ hours between ebb and flood tide; the foundation stone was laid on 19 August the following year by The Duke of Edinburgh, Master of Trinity House. The supply ship Hercules was based at Oreston, now a suburb of Plymouth; stone was prepared at the Oreston yard and supplied from the works of Messrs Shearer, Smith and Co of Wadebridge. The tower, which is 49 metres (161 ft) high, contains a total of 62,133 cubic feet of granite, weighing 4,668 tons. The last stone was laid on 1 June 1881 and the light was first lit on 18 May 1882.

Still in use today, its white light flashes twice every 10 seconds. The light is visible to 22 nautical miles (41 km), and is supplemented by a foghorn of 3 blasts every 62 seconds. A subsidiary red sector light shines from a window in the tower to highlight the Hand Deeps hazard to the west-northwest. The lighthouse is now monitored and controlled from the Trinity House Operations Control Centre at Harwich in Essex.